Childhood Sexual Abuse: A Biblical and Theoretical Examination

Childhood sexual abuse is a topic often avoided in social circles due to the discomfort it causes on the one hand, and the absolute outrage it evokes on the other. It is the topic of inappropriate humor or brushed aside as less than evil. Comments such as, “Oh, Uncle George is just a dirty old man” are whispered at family reunions, when what “Uncle George” has done to females in the family for generations is not only atrocious but illegal. It is irresponsible and immoral to turn a blind eye to the devastating crime of CSA. A voice must be given back to those whose voice – and innocence – have been brutally stolen by those more powerful. A stand must be taken against CSA, if not to stop it from happening, then in order to assist survivors who are haunted by their experiences. Evil is overcome by redemption, and redemption can be found if people are willing to look evil in the eye and say, “No more.” Individuals must study CSA – the causes, the effects, intervention, and treatment – in order to become equipped for the battle against it.

A Broad Look at Childhood Sexual Abuse

By definition, childhood sexual abuse entails a variety of characteristics. According to Glicken & Sechrest (2003), “Sexual abuse might be defined as a sexual assault on, or the sexual exploitation of, a minor” (p. 107). The abuse may take place only once or over an extended period of time. It may include one or more of the following acts: “rape, incest, sodomy, oral copulation, penetration of genital or anal opening by a foreign object, and child molestation” (Glicken & Sechrest, 2003, p. 107). CSA can also involve sexual harassment, exposure to pornography or taking pornographic photographs or video of children, and the sexual trafficking of minors. These acts are done for the sexual gratification of the perpetrator.

The statistics surrounding childhood sexual abuse are astounding. It should be noted that according to The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2004), as cited by Hodges & Myers (2010), these statistics are an underestimation of the actual figures because children are often afraid to report abuse and due to the lack of abuse validation. Hodges & Myers (2010) go on to reference the statistics as reported by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2000), stating that children make up 67% of all sexual assault victims; out of those children, those younger than 12 make up 34% and those younger than six make up approximately 15%. Additionally, in 2007 the National Center for Victims of Crime published that females are the victims of CSA three times more frequently than boys, and 25% of juvenile females will be sexually assaulted by time they reach 18 years of age (Hodges & Myers, 2010). Foster (2014) cites the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2005), stating that “one in six boys are sexually abused before the age of 18” (p. 332). Glicken & Sechrest (2003) report that males make up 23% of total sexual abuse cases. Facts and figures point to the staggering truth: childhood sexual abuse is rampant in today’s society.

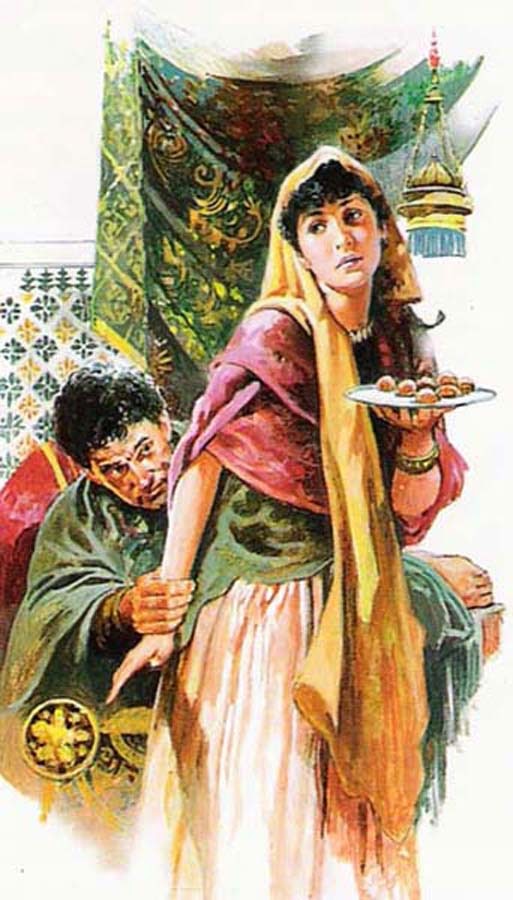

The existence of CSA is not exclusive, however, to modern day culture. The bible renders accounts of sexual assault, including rape, incest, and CSA. The book of II Samuel reveals the sexual abuse of King David’s daughter, Tamar, by her older half-brother, Amnon. Amnon was the oldest child of David; Tamar was approximately 15 or 16 years old at the time of her assault (Smith & Chapman, 2011). Scripture details the conspiracy between Amnon and his cousin Jonadab, who devised a plan to get Tamar alone with Amnon in his bedroom. Once they were alone, Amnon demanded that Tamar come to bed with him. She refused and even offered to marry him, if he would only ask their father’s permission. Instead, “Amnon wouldn’t listen to her, and since he was stronger than she was, he raped her” (II Samuel 13:14, New Living Translation). To make matters worse, after he raped his sister, Amnon’s so-called love turned to hate, and he threw Tamar out of his room. Sadly, the family covered up the scandal: “So Tamar lived as a desolate woman in her brother Absalom’s house” (II Samuel 13:20b, NLT); Amnon went unpunished by their father, and eventually, Absalom ordered the murder of Amnon. Like many women, Tamar reaped the guilt, shame, and destruction bestowed upon her by the abuser, never receiving the love, kindness, and godly presence it takes to lead a victim to restoration, redemption, and healing.

The Causes of Childhood Sexual Abuse

There are theories as to why perpetrators feel the need to sexually violate children. In the cases of incest, attributing factors include “dysfunctional relationships, chemical abuse, sexual problems, and social isolation” (Glicken & Sechrest, 2003, p. 119). Violators drawn toward children frequently do not tolerate frustration well, have little self-esteem, and need immediate sexual gratification. Most tend to repeat their mistakes rather than learn from them. Additionally, perpetrators of CSA have addictive personalities, little remorse for their actions, and excel at lying and manipulation (Glicken & Sechrest, 2003). There are no age parameters when it comes to child molesters. Pedophiles are specifically interested in sexually defiling children, believing that sex with children is “appropriate and even beneficial to the child” (Glicken & Sechrest, 2003, p. 120).

Who fits the profile of an abuser? Men, women, fathers, pastors, brothers, grandfatherly next door neighbors, teenage boys at the park, and older girls on the school playground can all be perpetrators of childhood sexual abuse. In other words, although it is more common for females to be abused by older males, one should not rule out men abusing boys or females sexually abusing children (Allender, 2008). Why do offenders sexually abuse children? Allender (2008) lists “excuses” that he believes should not exempt the individual from accountability for the crimes committed:

- The abuser was abused as a child.

- The abuser had a difficult background.

- The abuser was going through a rough time with his or her spouse and was lonely.

- The abuser drank so much that he or she was unaware of what he or she was doing.

At the very heart of sexual abuse is evil. Ephesians 6:12 reads, “For we are not fighting against flesh-and-blood enemies, but against evil rulers and authorities of the unseen world, against mighty powers in this dark world, and against evil spirits in the heavenly places” (NLT). The intent of evil is to destroy God’s creation. In the Old Testament, it is written, “So God created human beings in his own image. In the image of God he created them; male and female he created them” (Genesis 1:27, NLT). Furthermore, God created intimacy, perfectly reflected and expressed between a husband and wife within the sanctified bonds of marriage. Evil takes great pleasure in destroying that which reflects God’s image – mankind, and in defiling the most intimate of God’s gifts – sexuality. The harm done by CSA causes one to despise his or her own gender or to experience gender confusion, much to the satisfaction of darkness (Allender, 2015). As Allender (2015) describes it, “Evil delights in sexual abuse because the return on investment is maximized. It takes but seconds to abuse, but the consequences can ruin the glory of a person for a lifetime” (p. 36).

The Effects of Childhood Sexual Abuse

The effects of CSA do not diminish simply because the abuse has ended. In the Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, Foster & Hagedorn (2014) explain that “CSA frequently impacts children socially, cognitively, academically, physically, spiritually, and/or emotionally” (p. 538). Victims of abuse develop coping mechanisms that can come in the form of justifying the abuse, dissociation during abusive incidents, or in extreme cases, developing dissociative identity disorder (Vieth, 2012). The abuse is bathed in secrecy, and upon disclosure of the abuse, children may experience guilt when threats made by the perpetrator – such as being removed from the home, isolation, or disbelief – come true. Being taught to obey adults, there is much confusion when obedience puts the child in such a deviant position by the offender. Children believe that adults, especially those who should love them, can be trusted; CSA breaks that trust in others (Foster & Hagedorn, 2014).

There is a developmental impact on children as a result of sexual trauma. Because trauma impedes a child’s ability to control arousal levels, problems such as learning disabilities and aggression may develop (van der Kolk, Weisaeth, & van der Hart, 2007). Allender (2015) and van der Kolk, et al. (2007) touch on a similar point: the inability of the abused child to convey affect states in words. As Allender (2015) describes it, “Literally, during trauma, language goes offline” (p. 58). When trauma occurs, Broca’s area – that section of the brain where language is processed – stops working or drops in activity, similar to a stroke patient (Allender, 2015). Unfortunately, when the words cannot be formed, the images attack later in life in the form of flashbacks.

As sexually abused children mature, the damage of that abuse may be witnessed in different areas of that person’s life. CSA creates within that individual a sense of powerlessness, helplessness, and an undying pain deep within (Allender, 2008). If that pain is not addressed, the tendency is to adapt self-numbing habits, whether through outside sources such as drugs or alcohol, or simply through the hardening of emotions and isolation. There is a loss of the sense of self, as well as a loss of the sense of judgment. “Sexual-abuse victims have learned to doubt their own feelings” (Allender, 2008, p. 126). The adult victim of CSA often loses any hope for true intimacy, for strength, or for justice. Life is marked by ambivalence, which can further lead to depression, sexual dysfunction and addiction, compulsive disorders, and physical complaints (Allender, 2008). Biblically speaking, this makes sense: “Hope deferred makes the heart sick, but a dream fulfilled is a tree of life” (Proverbs 13:12, NLT).

The spiritual effects of CSA vary. In one study, it was discovered that children were spiritually injured, so to speak, due to the abuse they had experienced (Vieth, 2012). These children encountered “guilt, anger, grief, despair, doubt, fear of death, and belief that God is unfair” (Vieth, 2012, p. 261). However, not all spiritual effects were negative following sexual trauma; the same study showed that survivors prayed more often.

The Intervention of Childhood Sexual Abuse

Intervention and possible prevention of CSA begins with educating both children and adults. CSA education can be shared within schools, churches, and community centers; however, the education is only as effective as the accuracy of the information. Unfortunately, there are myths regarding CSA that can cause more harm than good.

Although “stranger danger” is an important rule to teach children, the facts show that perpetrators of CSA are more likely to know the child personally than to be a stranger. In fact, CSA occurs only 3-10% of the time at the hands of a person the child does not know (Foster, 2014). Programs should teach the pervasiveness of known offenders, as well as explain the warning signs of a possible abuser and the grooming tactics that violators use. It is crucial to teach that people who commit childhood sexual abuse vary, “in which most are known by their victims, trusted by their family, and do not have a criminal history” (Foster & Hagedorn, 2014, p. 552).

Another falsehood is that most sexual predators are adults. Studies have revealed that adolescents commit 33% of episodes of CSA (Foster & Hagedorn, 2014). Adults should be aware of certain characteristics of juvenile offenders, such as delinquency and impulsivity. In addition, adolescent offenders are often former victims of CSA; therefore, intervention is important for both the victim and the perpetrator.

Correspondingly, there is the myth that children can stop the abuser from attacking by utilizing tactics such as yelling “stop” or running away. One should never expect a child to be able to impede the plans of an offender bent on molestation (Foster & Hagedorn, 2014). To put that belief within a child can do more harm than good, especially if he or she is unsuccessful at stopping the abuse. Self-blame for CSA is already common; to put the expectation within children that they should have been able to avoid or prevent that attack of a pedophile would heap mounds of guilt upon the already existing fear, anger, shame, and grief.

Programs that educate adults and children about CSA can help intervene and prevent childhood sexual abuse. When taught about safety and healthy sexuality as opposed to victimization, the bonds between parents and children can be strengthened. This leads to trust, which boosts the chances of disclosure, lowers a child’s self-blame in the case of CSA, and promotes children’s self-efficiency (Foster & Hagedorn, 2014).

Treatment of Childhood Sexual Abuse

Once the safety of the child is established and medical attention has been provided (Glicken & Sechrest, 2003), it is imperative that a victim of CSA is not left untreated for the psychological, emotional, and spiritual ramifications of trauma. According to Glicken & Sechrest (2003), “Appropriate treatment and careful case management can often lead to successful outcomes and frequently end the multigenerational cycle of abuse” (p. 122). During crisis intervention, it is critical that the victim be reassured that he or she is not to blame for the abuse. Because of the complexity of CSA, other members of the family may require counseling as well. Any fears of disbelief, punishment, or revenge from the abuser must be addressed; as aforementioned, the child’s safety must be of top priority.

Therapists working with children who have been victimized by sexual abuse must remember that trust has been broken; therefore, it may be slow going in gaining that child’s trust (Foster & Hagedorn, 2014). Empathy toward the child’s worries can help to put the victim at ease. Counselors may support children to express their hesitancy and anxieties, share information about therapy, and reassure them that what they are feeling is common. It is important to be proactive when it comes to relieving the fears of the victim. In addition to educating the child, it is vital to advise the parents or caregivers about the counseling process. By letting them know the challenges that accompany counseling, it can prevent them from removing a child too soon if symptoms appear to worsen before improving.

One effective method of counseling is Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT). This is “an evidence-based treatment approach that is structured to include child-only sessions, parent-only sessions, and joint family sessions” (Foster, 2014). This type of therapy is conducive in meeting the developmental needs of the victimized child. The focus is on symptoms related to trauma, such as fear, anxiety, and depression, in children ages three through 18, using gradual exposure. Per Foster (2014), the eight components of TF-CBT are as follows: psychoeducation and parenting skills, relaxation skills, affective regulation skills, cognitive coping skills, trauma narrative and cognitive processing, in vivo mastery of trauma reminders, conjoint child-parent sessions, and enhancing safety and future development trajectory.

From a Christian perspective, Vieth (2012) provides guidelines in ministering to a victim of childhood sexual abuse. First, if the child is older, or if this is a case where an adult has come for counseling when processing his or her own CSA, put judgment aside and do not focus on the victim’s sins. It is not uncommon for the lives of abuse survivors to be tainted by drugs, alcohol, divorce, crime, sexual promiscuity, or mental illness (Vieth, 2012). Quick judgment and harsh rebuke will push the victim away. Instead, love should be poured upon the survivor of CSA, putting the gospel into action and standing with the broken. Isaiah 61:1b reads, “He has sent me to comfort the brokenhearted and to proclaim that captives will be released and prisoners will be freed” (NLT). God wants his people to comfort the victims of childhood sexual abuse, releasing them from the fear and captivity of their trauma.

Survivors of CSA must be shown Christ’s empathy (Vieth, 2012). Victims may question the goodness of God. The counselor can explain that the offender disobeyed God’s commandments. Victims need to know that Jesus understands maltreatment, emotional abuse, and physical abuse, as portrayed by His journey to Calvary. Sharing scripture about Christ’s love for children may reassure the survivors that God does care about them. In Mark 9:37, Jesus said, “Anyone who welcomes a little child like this on my behalf welcomes me, and anyone who welcomes me welcomes not only me but also my Father who sent me” (NLT). Regarding the harm of children, Jesus said, “It would be better to be thrown into the sea with a millstone hung around your neck than to cause one of these little ones to fall into sin” (Luke 17:2, NLT). Luke 18:16 reads, “Then Jesus called for the children and said to the disciples, ‘Let the children come to me. Don’t stop them! For the Kingdom of God belongs to those who are like these children’” (NLT). If the Lord cares so deeply for children, then those in the Christian community should provide the care and protection needed when one of God’s little children has been abused.

References

Allender, D. (2015). Healing the wounded heart: The heartache of sexual abuse and the hope of transformation. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

Allender, D. (2008). The wounded heart: Hope for adult victims of childhood sexual abuse. Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress.

Foster, J.M. (2014). Supporting child victims of sexual abuse: Implementation of a trauma narrative family intervention. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 22(3), 332-338. DOI: 10.1177/1066480714529746

Foster, J.M., Hagedorn, W.B. (2014). Through the eyes of the wounded: A narrative analysis of children’s sexual abuse experiences and recovery process. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 23(5), 538-557. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2014.918072

Glicken, M.D., & Sechrest, D.K. (2003). The role of the helping professions in treating the victims and perpetrators of violence. Boston, MA: Person Education, Inc.

Hodges, E.A., & Myers, J.E. (2010). Counseling adult women survivors of childhood sexual abuse: Benefits of a wellness approach. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 32(2), 139-154.

Smith, R.P., & Chapman, C. (2011). II Samuel. In Spence, H.M.D., & Exell, J.S. (Eds.), The pulpit commentary: Ruth, I & II Samuel (Vol. 4) (pp. 1-637). Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers Marketing, LLC.

van der Kolk, B.A., Weisaeth, L., & van der Hart, O. (2007). History of trauma in psychiatry. In van der Kolk, B.A., McFarlane, C., and Weisaeth, L. (Eds.), Traumatic stress: The effects of overwhelming experience on mind, body and society (pp. 47-74). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Vieth, V.I. (2012). What would Walther do? Applying law and gospel to victims and perpetrators of child sexual abuse. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 40(4), 257-273.